Systemic Complexity in Business: More Than the Sum of the Parts

Categories Complexity, Systems Thinking

For years the dominant view of organizations has been mechanistic; a company should run like a clockwork, the cogs just needed to be aligned to fit, run smoothly and with least possible friction. Anyone who has dared enter the murky waters of organizational behaviour will agree though that this is a gross over-simplification of a very complex system.

In the second part of our complexity series we will look at organizations through the lens of systems thinking. We will explore why approaching an organization as a complex system is challenging but why it also provides CEOs and senior executives with crucial insights to make sense of the often unpredictable dynamics within their organization.

The Company - A System With Peculiar Properties

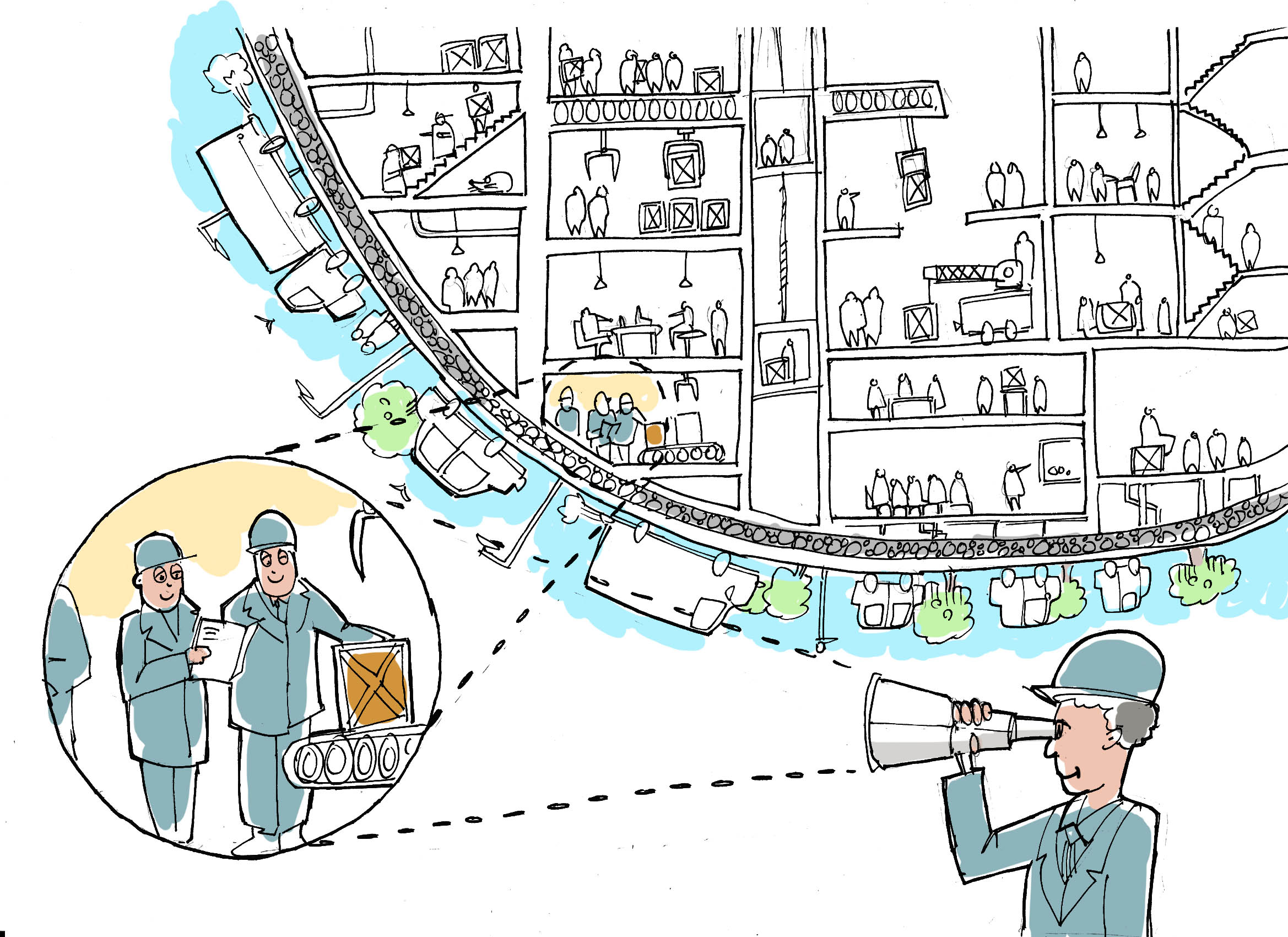

Any organization is in itself a system - a conglomerate of different interlinked bits and pieces that ideally work hand in hand to create powerful outputs. Take for example a candy factory: product development discovers new creations built from sugar and food colouring, production turns the designs into reality at scale, marketing spreads the word and stirs the appetite of the kids on the playground, the sales department makes deals with the candy stores and finance channels income into running costs and investment to keep the system running.

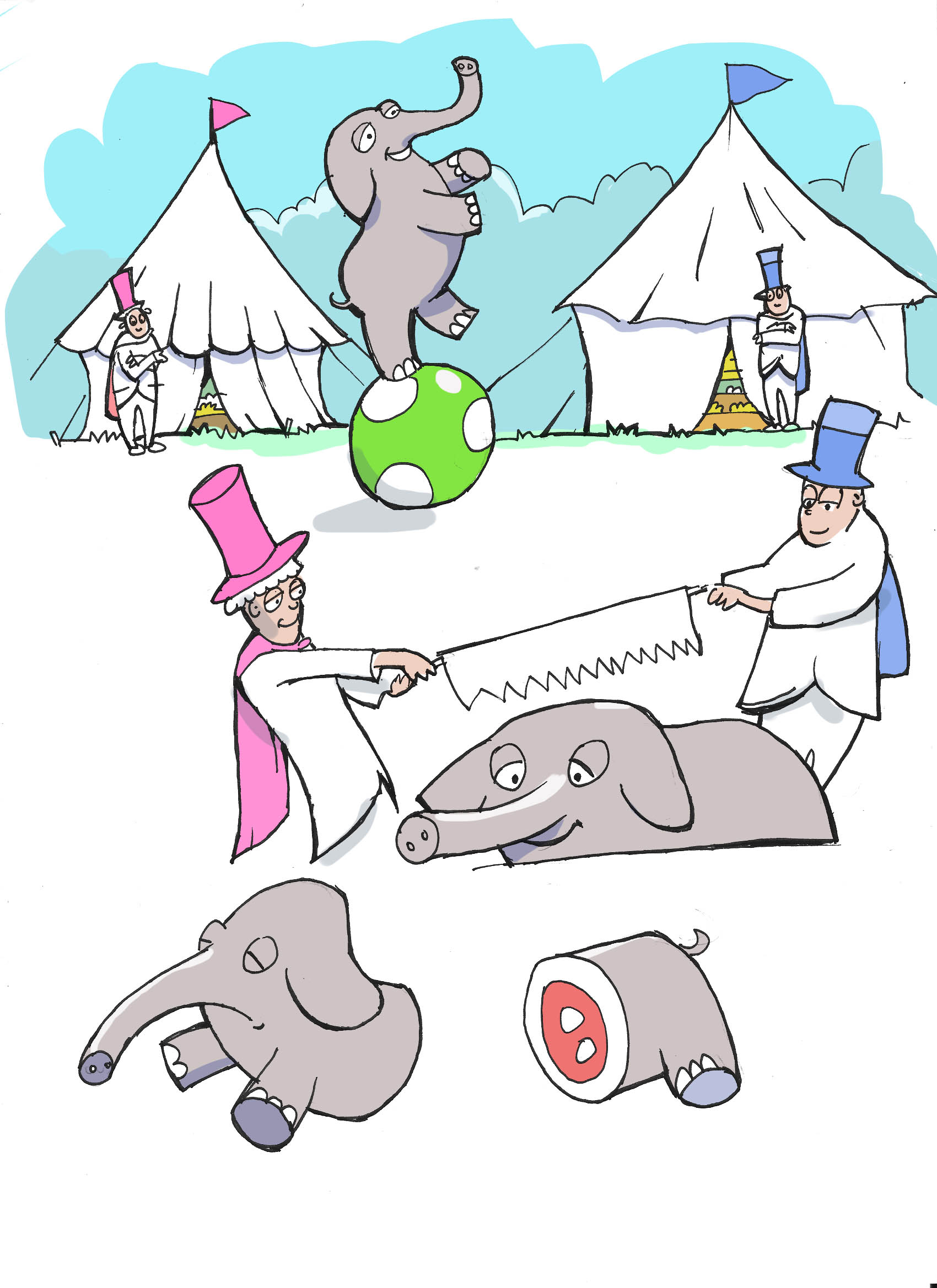

All these various functions or departments are interdependent, none could succeed without the other and together they form something that is greater than the sum of its parts - like the many different cells it takes to form the body of an elephant.

Where their efforts aren't aligned the system starts malfunctioning. Production can't keep up with an over-energetic sales force, marketing misrepresents product features, finance can't fund the new production line quickly enough.

Trade-offs are required not just between competing priorities but between today's operational needs and future plans.

A system has properties each of its parts alone does not have. The whole is a lot more than its various components; an organism with a purpose, an identity, structure and culture, behavioural pattern and its own unique dynamics and interactions.

Part of the challenge for senior executives is balancing all these factors to create a stable and productive organization.

'Dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants.'

Peter Senge, 'The Fifth Discipline'

By design an organization is a complex system. It is composed of many diverse elements which are exposed to change and variation and which continuously interact with each other in sometimes unpredictable ways. And - to make things even more complicated - there are smaller sub-systems within the big system.

The components of these systems fall roughly into two categories: technical and human.

Technical Components of the System - The Easy Battleground

A key element of your organization are the various technical systems and components that allow you to operate efficiently. The production line, the CRM system, the accounting software are all technical sub-systems of your organization. Ignoring for the moment the weary promises of artificial intelligence, these technical systems are mostly predictable, and even though complicated are relatively easy to handle. They might challenge you logically but at least they don't have an opinion you need to battle with. Process improvement frameworks such as Lean, Six Sigma and Total Quality Management all target these hard systems with the aim to continuously optimize them to reduce waste, improve quality and gain efficiency. When operations managers talk about systems design, this is usually what they refer to.

Human 'Components' of the System - The 'Uneasy' Battleground

Anyone who has been tasked with implementing a change program knows from painful experience that changing the human elements in the system is a lot harder. Human systems are inherently more complex than technical systems. They are much less predictable, much harder to understand and much more difficult to influence. And often meddling with human systems forces us out of our own comfort zone, making us feel rather uneasy.

The problem is that human systems are composed of human beings. Every single person in an organization comes with significant baggage. Unlike the candy packaging machine that only connects to the feeder, the wrapper and the electricity outlet, your average employee is connected to their job, their desk, their boss, the secretary, their spouse, a bunch of kids, the local rugby club, their mother in law, the bank, their past, their dreams, ambitions, fears, worries, financial constraints, jealousies, expectation and countless other aspects of their life.

These life experiences influence people's neurological responses to their work environment in subtle but powerful ways - either enhancing or undermining the rational argument for change. In short: they define how we are 'wired'.

Since humans are complex they are often unpredictable by rational standards: informal human systems can overwrite the rules of formal hierarchies and relationships and emotional responses can disrupt the most rational strategic plan.

But don't despair! Human beings are the most challenging element of any system but they are also the most powerful. Provided you manage to break through the noise and confusion and gain access to your team's passion and motivation, once you get your employees truly fired up for an idea, they become problem solvers, innovators and inventors. They find solutions to problems you haven't even discovered yet and they can make your entire organization fly - while the packaging machine is still just wrapping candy bars.

Harmonizing the collaboration of the many components of your system - human and technical - within the environment you operate in, driven by a joint vision and purpose, and with the aim to achieve true excellence, that is what change leadership is all about. That is where your capability, as a leader, to manage systemic complexity needs to kick in. Both your cognitive power and your emotional maturity will need to be highly-developed to understand the challenges and take the necessary decisions.

by Antonia Koop