In the first three parts of our series on complexity we have focused primarily on framing what we mean when we talk about complexity and we have begun exploring the demands increasing complexity poses on leaders and senior executives. In this fourth part of the series we will start to look into the particular capabilities executives need and how they can be developed.

Last month my colleague, Jim, told me how, on leaving his client’s HQ after another consulting day, the CEO approached him and asked, ‘how can I get my senior team to expand their thinking?’

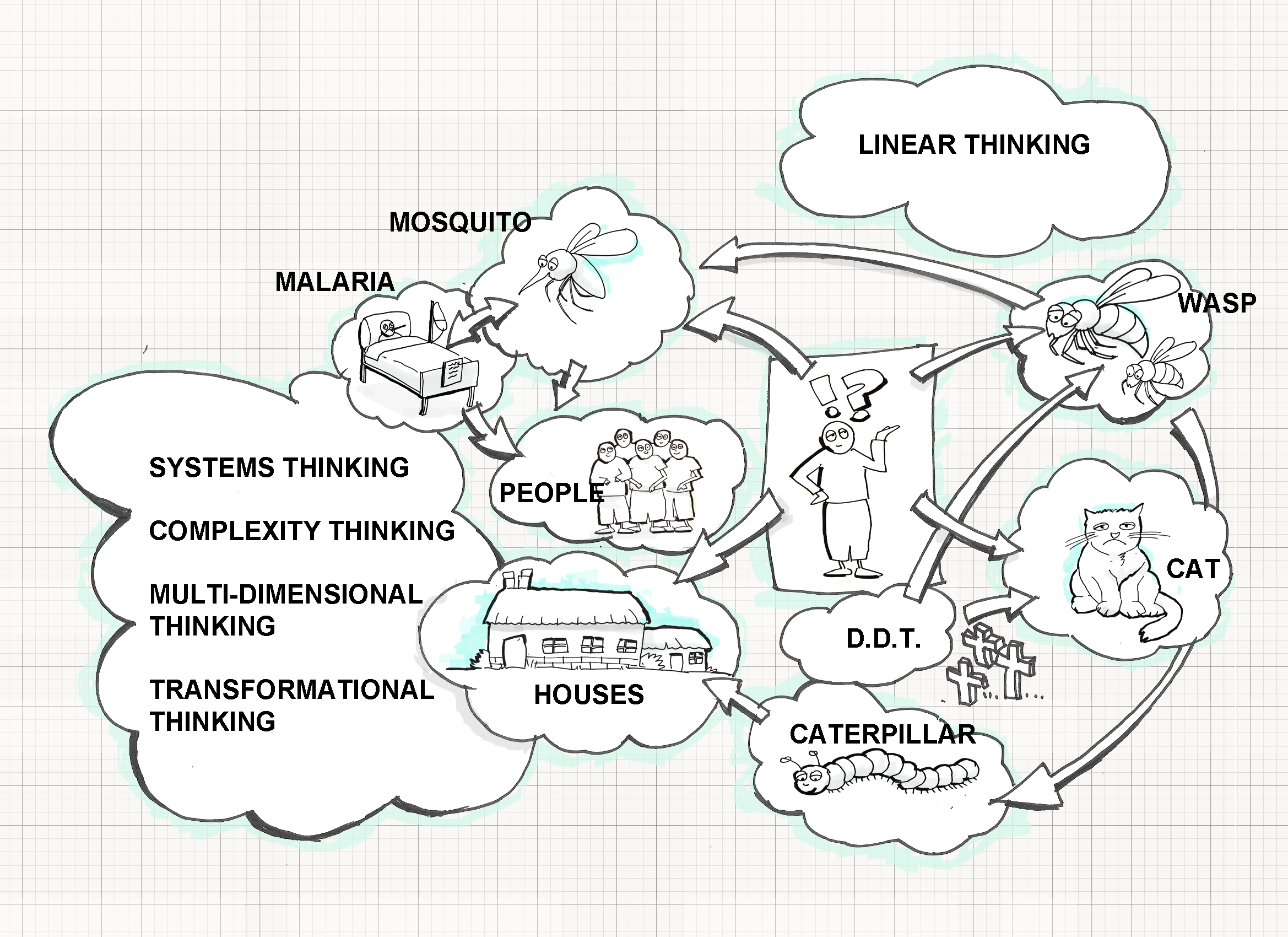

Jim understood the problem the CEO had raised. The team in question was facing a great deal of uncertainty about the company’s future direction. They were considering problems which they had never encountered before. They had been applying their usual cause-effect analytical approach but still couldn’t grasp the scale of the opportunities and risks in the external market. The CEO was becoming increasingly frustrated. If he could understand the problems, why couldn’t they?

The company had always been successful in recruiting people with excellent specialist skills and had paid careful attention to the blend of personality and work styles which would help to create good working relationships. However, at the higher organization levels where people were moving from operational to strategic work, not everyone coped well with the transition. Despite their best efforts at rigorous selection and development the company was unaware that, at these higher levels, a subtle shift in thinking capability was also required to cope with the increased complexity inherent in these roles.

What is ‘thinking capability’?

‘Thinking capability’ is a frequently-used but often ill-defined concept. Sometimes confused with IQ, or presumed to be measurable through ‘critical thinking’ tests, it addresses the critical question: ‘how well can this person cope with the complexity of their work?’ The ground-breaking research of Dr Elliott Jaques and his colleagues discovered that ‘thinking capability’ is essentially about information processing and that work roles at different organizational levels contained differential levels of information processing complexity: defining a problem and constructing pathways towards resolving it looks very different at, say, first-line team leader level to Business Unit President level. We know, intuitively, that some roles are more complex than others but we often cannot say why or how to measure that difference.

CIP (Complexity of Information Processing) is the engine that drives the car. CIP is the raw cognitive processing power within us which matures at a predictable rate over our lifetime. As we move in our working journey and encounter more complex work, the rate of our CIP maturation will, hopefully, match the increasing complexity of each higher role.

Where there is a match, we can feel ‘in flow’ with our work: challenged and stimulated but still able to cope. However, where the role demands a higher level of CIP than we currently possess then we feel over-stretched, stressed and need a lot of support to understand problems and make decisions (as Jim’s clients were finding). The reverse situation is also problematic. In those cases where our CIP level is higher than the role requires, we feel under-challenged and frustrated.

The question arises: how can we identify the match between people and their roles in terms of CIP in our talent assessment process? How can we stretch people’s thinking capability to prepare them for more complex roles? Our belief is that we can accelerate the CIP maturation process through experiential games-based learning and specialist developmental coaching which expose people’s minds to greater complexity.

This belief is what drives us in our business - because the world needs more strategic thinkers for the unprecedented challenges we face.

by Christine Baker